It was a bizarre contradiction to Shay (a user of They/Them pronouns) that the grand success of human beings was apparently premised on the supreme ability of the species to cooperate with one another. Whoever had come up with the theory was clearly not experienced in the real-world shit show of getting people to work together on anything. The fact that anything ever managed to happen in the world was miraculous when you got behind the scenes to see the utter shambles inherent to any system of organisation. Still, for some reason unfathomable to Shay Themself, They remained committed to this against-all-odds miracle, which occasionally occurred to create new ways of doing things based on the magic of collaboration.

But right now, Shay was tired. They’d essentially been bundled up by a few members of the Care Collective, and hauled off from a protest camp to the Care Collective’s land project on a windy hilltop in the middle of nowhere, the name of which was Pen Coed. “You’re going to get burned out if you carry on like this,” various members of the Care Collective had insisted. “You need to step back and detach before you make yourself sick.” At the time, Shay hadn’t really known what the Collective members were talking about and felt like They’d been kidnapped from Their life’s work. But after a week of forced retreat, the tiredness had started to kick in. At first, Shay resented it; They hadn’t felt this tired before They came here. Surely it was the not doing anything that brought on the tiredness? “Just go with what you feel,” people kept telling Shay. “If you’re tired, go and rest. You don’t need to push yourself out of it.” Eventually, Shay started to concede that the Care Collective had seen something in Shay that Shay hadn’t been able to see in Themself.

Not that the Collective itself had everything figured out. It had adopted some strange way of trying to organise lately, and Shay was pretty sure it wasn’t taking the group anywhere. The name of this process was “Elevated Together.” As far as Shay could make out from fairly abstract descriptions, it was about getting to the very bottom of any tension or conflict that existed in the group so that some kind of state of perfect harmony could be reached, and the group could then go forth together as One; as a single arrowhead slicing through the air to its target. The problem was that there was never any real bottom to get to; only false floors that gave way to ever deeper caverns. The members of the Collective would remain in sessions behind closed doors for hours and emerge looking tired and worn, only to go back the next day to try to get to the bottom again.

That afternoon, the Collective was in session, and although Shay doubted the process, They didn’t mind the less busy atmosphere while most people were shut up in one room. There were other visitors around, but all were keeping to themselves. Shay went to sit in the project’s large greenhouse and braid together the onions and garlic that had been gathered in from the harvest at the end of the summer and left piled up in trays. There were several acres of fertile land around Pen Coed’s main house, and the Collective managed to grow a decent amount of food. Braiding the garlic and onion was soothing work; physical without being taxing, and satisfying in that the long braids that Shay produced could then be hung up indoors for use throughout the autumn and winter. As Shay worked, They enjoyed the gentle thoughts that were starting to ebb through Their mind after a couple of weeks out on the land. It was a time to get perspective on things. Overhead, a raven made its rich, throaty cry, and Shay felt a certain peace.

As Shay braided, They reflected on what didn’t work about ‘Elevated Together.’ The way that Shay saw things, collectively doing anything at all was always some kind of rough approximation; harmony was but a brief experience of a moment in time, a fleeting sense of stillness and joy before everything careered out of whack again. Getting to the very bottom of things within a group meant that nothing would ever go forward in the outside world, and Shay had expressed as much to members of the Collective.

Yet this was not to say that Shay had no belief in group process. There had to be processes to see a group through the aggravation of collectively trying to achieve a goal, especially if that goal went against the grain of the wider culture. There had to be ways to make decisions together, to process the endless wheel of group dynamics, of privileges and petty hierarchies playing themselves out, and to deal with the fact that if you’re trying to precipitate any kind of social change, you’ll be faced with monstrous levels of hostility – from institutions such as the police, from the media, from the average person on the street.

It was Shay’s magical superpower to hold groups through this process. Shay had a powerful sense of what was happening in a room, of how a group became its own special entity; it was never static, always shifting and morphing. Shay’s job was to absorb all of those crazy energetics, synthesise everything going on, focus the group on moving through each barrier and block that came up, whether emotional or pragmatic, and move the group towards action again.

At the same time, Shay’s greatest strength was inextricably linked to Their greatest weakness; because They had this incredible capability to hold space, They believed They could do it alone. To some extent, there was truth in this, but realistically, and in the protest camp from which the Care Collective had extricated Shay, They absolutely could not. Things at the camp had gone really wrong. Shay’s circle of support – the other facilitators and space-holders – had one by one dropped out, and Shay had been unable to take that as a sign that They shouldn’t be pushing things forward on Their own. They could see that things were starting to get chaotic on many different fronts, but They kept pushing anyway, all the while getting more hyperactive and less grounded. Ultimately, things ended up in a toxic mix of poor decision-making in the group, leading to avoidable police arrests. A lot of the blame for this was heaped on Shay for apparently becoming the dominator of the group, which Shay had fervently objected to.

A couple of members of the Care Collective had arrived late on the scene at the protest camp. The Collective was always spread thin across a whole lot of activist struggles, and they arrived at Shay’s camp to find a broken down group filled with anger and hostility and a Shay who was so wired that Their actions were only worsening the situation. It had taken a lot to talk Shay down, to convince Them that it was time to go and that people could be left to work out their own shit. The two of them plied Shay with a load of nervine herbal tinctures, wrapped Them up in blankets and persisted until Shay went to rest in the back of Their live-in vehicle before driving Them back to Pen Coed.

And now that Shay’s mania had subsided, They could start to admit that this had been the right thing to do. In spite of the Care Collective’s bizarre ways of doing things of late, Shay felt a deep appreciation of the Collective and of Pen Coed as a whole. Shay had spent brief amounts of time in Their fair share of other rural land projects and found the inward-looking nature of these projects hard to tolerate. The dynamics between people were often frosty and brittle. Everyone seemed to have an insurmountable need for space – even though living in a rural land project meant you already had more space than anyone in the city. People seemed to endlessly discuss the ethics of such minutiae as whether the project should purchase soya milk in non-biodegradable tetra packs from crops grown on the other side of the world or local milk from the farmer over the hill produced by oppressed and evil methane-farting cows. And worst of all, there was an unwillingness to share the incredible privilege of living on the land with everyone holed up in the city.

Pen Coed was, for the most part, different. Certainly not perfect. Over the years, the project had faced times of terrible turbulence. There were also chronic money problems; never enough coming in to keep on top of all the maintenance work. The Care Collective, which was central to Pen Coed’s work, sometimes got things wildly wrong and was accused of parachuting into situations with little understanding of how things were working on the ground. And this Elevated Together nonsense – well, hopefully that wouldn’t last too long. Still, at the heart of the project was the value of being in service wherever possible to people and groups who were desperately trying to change things – by providing space at Pen Coed for people to regroup, and out in the wider world by giving support and care when this was lacking in a situation. And the project had a huge strength in committing to an ethic of processing and learning from mistakes.

Not only that, but Shay didn’t have to worry about how Their gender was perceived at Pen Coed. This was a welcome relief from the ‘Is it a boy or a girl?’ commentary that Shay was accustomed to. Shay was the kind of non-binary that seemed to trip people up and scramble brains; people couldn’t fathom not being able to place Shay on one side or the other of the gender binary. This highlighted society’s unhealthy obsession with gender norms, and Shay commonly received anger and abuse. Spending time on land projects was in some ways better, and in some ways, it felt like the binary was further enforced. Cis guys would stride about with an air of being rugged and strong, shifting all sorts of stuff from A to B and back again. Flowy-haired cis-women would run womb rituals they believed every woman should be involved in. In contrast, Pen Coed was quite the gender-jumble, and the part of Shay that was usually on the defensive could let go in the space.

The light was fading as Shay finished off Their last garlic braid. A buzz of energy picked up; doors opened and closed, voices burbled, and objects were being moved around. The Collective must have come out of the processing session. Shay made Their way up to the main house to help with the dinner prep that would need doing. There would be squash to hack up with an irritatingly blunt knife for a stew and dough to knead for bread rolls. After dinner, as the night was clear, there would be a fire outside, and the sparks would drift up to join the sparkling starlight. There would be music and laughter, and Shay would goof around with the others until late before heading back to Their van to curl up and drift off to sleep as the tawny owls hooted.

Somehow, the weeks slipped by at Pen Coed, and by then, Shay felt the time was coming to head back out into the world. Many members of the Care Collective had asked Shay to stay on and join Pen Coed. Shay had no rational reason as to why They should leave, just a pull at Their heart to follow Their own sense of purpose. Not that Shay really knew what that looked like in reality right now. But They felt that They had managed to ground and heal in Their time at Pen Coed. In providing sanctuary, the project had done what it was supposed to do for Shay. And now it was time to go. Shay hated goodbyes and would have gladly ducked out without any fanfare, but the Collective threw Shay a party on Their last night, and there was chaotic dancing and too much cider. It went on till late, and Shay slept only a few hours before making Their getaway at daybreak while everyone else was still sleeping. As They eased Their van down Pen Coed’s bumpy track, Shay felt Their own smile ripple through Their body. Some tears trickled as They drove. Thank you, Shay whispered. Again They felt strong.

It was back to the tarmac. All around the roadside edges of an ancient sprawling cemetery were the van and caravan dwellers, at perpetual risk of being evicted by the City Council, but really, where could people be moved to amid a housing crisis that pervaded the whole country? Shay was surprised at how many more live-ins had parked up there since They’d last been there several months back. At first, They fretted that They wouldn’t be able to find a spot as They always had before. But several people agreed to shuffle vehicles into different positions, and Shay made it in – just. Shay felt happy to be back there despite the harshness of life parked up in the city. Old friends and familiar faces, excitable dogs that Shay had missed, the gossip about what was happening and with whom, new people to get to know.

However, this was as far as the army’s influence went for Shay. When They were fourteen years old, Their father was deployed to Iraq. Some months later, he was killed under friendly fire. Shay might have been young and entrenched in the army way of life, but They had always been astute; They had known that there was something off with that war. To lose Their father to a war that was waged so flagrantly under false pretences meant that Shay lost Their belief not just in the authority within the military but any kind of authority, forever. To lose Their father to friendly fire was stupidity beyond words, and the anger drove Shay forward every day.

After Shay’s father was killed, Their mother fell apart for a long time. Shay was the one who kept the family going forward. They had three younger siblings who all needed care and attention, a mother who was lost in pain, and a new life for them all to work out, now that they could no longer live in military accommodation with the community-based way of life it entailed. This was how Shay started to do what They did. With Their belief in authority shattered, Shay couldn’t take that kind of leadership within Their own family. There would be no ordering anyone about. There was only figuring out how collaboration could work.

Shay realised They could take leadership in sharing a vision for a shared goal. Shay’s vision was for every family member to live well. This was woven into everything that Shay said and did. They would not let anyone keep falling, and everyone would come to understand that they must weave this vision into everything that they did, too. Shay became highly attuned to when things were starting to fray at the edges and when the work needed to be done to refocus and strengthen. There was no space for bullshit. Only honesty and directness and sticking with things until a resolution had been reached. Otherwise, everything would fall apart.

Shay had stayed close to the family home until Their youngest sibling, Maya, was all set for university. Maybe this had been overkill; the middle two had already left to lead their lives. But before Shay could leave, They had to know for sure that Maya was on track. When that time finally came, Shay knew They needed a big change in Their life. They bought a van and took to the road and never looked back. That was seven years ago now.

And now here They were, back in the live-in community. Somehow, it just worked for Shay. There was generally some chaos and drama amongst the vehicle dwellers, but Shay could usually avoid anything that had little to do with Them by hunkering down in Their own van. It was the kind of personal space that wasn’t the same as being boxed up in a block of flats; people in Shay’s community were a part of each other’s lives. There was company when you needed it and gossip, and people looked out for each other, even if there were sometimes shouting matches. Shay needed the daily connection that was mostly hard to come by in privatised neoliberal culture. And for that, Shay was willing to make the trade-off of more noise and drama than They’d otherwise have to deal with.

Shay spent the first few days back in the city working out logistics like food, water, and waste disposal. Really though, Shay knew that They needed to work out what They were going to do about money. They had been living on savings for a while, but the soaring costs of everything meant that things were getting tight. Plus, as always, They needed money for work on Their ageing van. They asked everyone They came across for leads on gainful employment and asked those people to ask others, too. Shay was incredibly well connected in the city, and the message spread as if along a mycelial network. It was far superior to the drudgery of internet searches and online forms.

After a few days, a message was relayed back to Shay. The community centre in the next neighbourhood was trying to set itself up as a ‘Welcoming Space.’ Spaces like these were being set up all over the place to fend off the worst aspects of the Cost of Living Crisis, especially as so many could no longer afford to heat their homes over the winter and needed somewhere to get warm. The community centre hadn’t got very far with getting organised; the centre manager was off work with stress, and due to the country-wide crisis in staff shortages, no suitable cover had been found. Apparently, things at the community centre were pretty shambolic and were set to get worse. The season hadn’t yet turned particularly cold, so people weren’t so far coming in large numbers to keep warm. But come they would, and the centre was far from prepared.

For Shay, the job was a shoo-in. Someone had already put in a good word on Shay’s behalf, and when Shay turned up to introduce Themself to the receptionist, the look of relief on his face was unmistakable. “Thank god you’re up for this!” said the receptionist. Shay didn’t know what it was They were actually up for but decided to just go with it. “We’ll need to get you to fill in a brief application, and a couple of the trustees will give you a short interview. But that’s just so we’ve followed procedure. Really, the job’s yours, at least for the next few months till the manager’s back. We’re so grateful to you for taking this on!” Right then, thought Shay, seems like the next challenge is here…

And what a challenge it was. Upon taking a tour of the centre, Shay couldn’t believe it hadn’t already been shut down. An area of the roof was leaking, and water seeped down one of the internal walls, leading to the growth of black mould. The heating system was faulty, due to an ageing boiler, and poor insulation and crumbling walls led to the centre being draughty and cold. The toilets were blocked due to persistent plumbing problems, and only one was properly functioning. The fire door didn’t work. The Disabled access was inadequate. There were miscellaneous piles of stuff everywhere that hadn’t been sorted through. The internet connection was appalling, and the printer was functionally useless. Yet there were plenty of people around the building using the downtrodden facilities.

When Shay looked through the centre’s accounts, They started to get an idea of where things had gone awry. A couple of years ago, some sources of grant funding had dried up, and Council funds had been severely cut back. Shay found quantities of applications for further funding that the centre manager had made, but hardly anything had come through. The only substantial funding of late had been given to run the Welcoming Space, but that didn’t deal with any of the deeper problems. No wonder the manager was off sick. Crap, Shay hadn’t anticipated any of this when They’d been told that the centre needed organising to be a Welcoming Space. Where to begin?

Shay started where They always did: talking to people and holding space. They needed to know more about what was already happening, what had already been tried, and what people would be willing to do to get on top of the situation. Most importantly, They needed to work out what the vision was that people could get behind and push for. And somehow, Shay had to be sure not to tread on anyone’s toes; not to crash into a situation with all its pre-formed dynamics acting like a superhero, while actually making everything worse.

It took a couple of weeks of conversations with locals and people involved in the community centre, then several community meetings which Shay facilitated, to get to the point: people wanted to see a thriving community centre that could serve a range of community needs, especially through the winter months. Lots of people had already been working on trying to achieve this, but there were some tweaks needed to get everyone pulling in the same direction. The funding constraints for the Welcoming Space and the imminent winter meant there was a two-month time frame to get it together, which provided a focus. But the thing that had been getting in the way until then was that the funding was only for the Welcoming Space and not to deal with the multiple issues of the building. How could the Welcoming Space be set up when there was only one functioning toilet and water running down the wall?

Over the next weeks, Shay worked with the community to start a campaign to ‘Save Our Community Centre for the Winter,’ and a big push was made to raise money through fundraiser nights and crowdfunding. This brought in enough for various bodge jobs on the building. Shay called in some favours from people who’d spent the 1990s squatting buildings and were adept at patching things up and getting them working. Was it all legal? At this point, Shay didn’t worry about that too much.

However, bodge jobs weren’t going to cut it for the longer term, and Shay swallowed hard at what They could see would need to happen at some point: going cap in hand for Philanthropy – money from the wealthy. This wasn’t the priority at that moment, but Shay knew They’d have to start working on it. Maybe there could be a children’s art exhibition in the wealthy part of town, with a plea for a large donor to step in during these hard times for the poor, starving children of the unfortunate areas of the city who don’t even have enough money for private schools. Maybe someone would step in and make an anonymous donation, and there’d be no need to grovel in gratitude for the money the donor had no doubt inherited from dubious origins in the first place. But for now, it was all about getting through the winter months.

A couple of months later, somehow things had just about come together. The plumbing had been sorted out in the toilets. Some parts had been replaced in the ancient boiler, meaning that with a fairly huge amount of good luck, it would keep cranking on, keeping everyone warm until there were the funds for a new one. The roof was patched up, and the worst drafts had been blocked. The fire door now functioned, and Disabled access had been updated. Even the internet connection had been improved, though getting the printer to function still eluded anyone who gave it a shot. A few community centre clean-up days had been organised, which also served to get people to sign up to volunteer for the Welcoming Space.

For the Welcoming Space itself, Shay had ensured that everything was covered as fully as possible. There was adequate seating, space for buggies and shelves with donations of books and games. A quiet room was set aside for people who didn’t deal well with a busy atmosphere. With some extra crowdfunding, Shay managed to stretch the budget for a crèche for a couple of hours a day to give worn-out parents a break. Volunteers who were trained in first aid were signed up to help run the space. A rota of advice workers from agencies around the city was organised, as this had apparently disintegrated in the last months. There was also now enough kitchen equipment to commandeer the ex-squatters from the ’90s to come and relive their glory days by cooking up a storm in the cafe every day. They mostly used food donations from veg box delivery schemes that customers would have complained about receiving, but were still edible.

Even for Shay, this was a huge feat of organising. They’d spent hours talking to people, both in person and on the phone, day after day, pulling strings, problem-solving, calling in favours, talking people into sparing a couple of hours a week who were already insanely busy (of course, everyone was already insanely busy), dealing with tensions and conflict, cutting corners, ignoring red tape. Hopefully, Shay would be out of there before anyone started complaining too much about Their unconventional way of doing things.

In truth, Shay hated the whole situation. Everyone was being forced to bend over backwards, do more and more with less and less, and be endlessly creative just to get the basics. Nobody was truly being held accountable for the fact that people couldn’t afford their basic amenities. It was all completely unsustainable. Everything teetered on a knife edge. If a Covid outbreak occurred, what then? What if someone fell seriously ill in the community centre and no ambulance came because of the healthcare crisis? Not worth thinking about, just keep crashing on. Deal with things if they come up.

When it finally opened officially as a Welcoming Space, the day-to-day at the community centre was more or less the same, at least for the first couple of weeks. People came to use the computers, drink tea and get food from the Food Bank, which was set up in the main room on Tuesdays and Fridays. Shay felt very conflicted about the Food Bank; it seemed to restrict people’s access to food about as much as it actually provided food. People were three vouchers in every six months to attend the food bank before they were supposed to have found a way to stabilise their income. This was apparently to reduce dependency on the food bank, but it was as if the policy was attempting to get people to reduce their dependency on food itself. Shay had no idea how to challenge this and kept their mouth shut.

Then, in the third week of the Welcoming Space, the temperature plummeted, becoming uncharacteristically cold for the time of year. The centre suddenly got intensely busy. A huge range of people came: single parents and their young kids, older people, unemployed people, homeless people, Disabled people, black and brown and white people, all unable to afford their extortionate heating bill, if they had a home at all. The most surprising thing was to see people who looked more middle class waiting in line, and it took Shay a while to realise that this was because those people were now spending everything on their mortgage costs and could no longer afford food and fuel.

After a short time, Shay recognised there had been a huge oversight in planning; people were coming in drunk and rowdy, and there was nothing in place to deal with the potential antagonism that could emerge. The realisation hit Shay that They were falling into the same old pattern of trying to do too much on Their own, and They set to drawing in more people who were skilled in dealing with intoxication, who could train volunteers in how to ensure that a situation did not become inflamed with confrontation. It wouldn’t be easy, but everyone would have to find ways to manage, making sure that people weren’t turned away just because they were intoxicated, and at the same time, ensuring that drunkenness wouldn’t dominate the space.

As time passed, certain norms became established in the space, and people learned to navigate one another despite being very crowded. There were even regular community meetings that anyone could participate in to help manage the smooth running of the space. It looked like the winter might pass without too much incident, but in mid-February, several factors suddenly made everything more extreme. In the last weeks, there’d been further hikes in interest rates, energy prices and food costs. People who had until then been scraping by now had to make applications to use the Food Bank, and were coming to get warm in the Welcoming Space. It was also the half-term holiday, and whole families were coming for lunch due to the absence of free school meals in the holidays. After a mild spell, the weather had again turned very cold, so usage of the Welcoming Space had gone up again. And to make matters worse, as the queues for the Food Bank got longer, the Food Bank itself was running low on supplies due to a drop in supermarket surpluses.

It was a Tuesday morning and Shay could feel the crackle of tension in the air as people queued to use the Food Bank. Shay felt ill-prepared for whatever was about to occur. Suddenly, there were raised voices and jostling towards the end of the queue. Someone yelled, “I’m just sick of foreigners taking the little we’ve got all the time, and pushing in front of us to get it!” to which a tall guy with a Polish accent turned round and boomed, “Fuck you, I am British citizen now!”

Shay needed to act fast to prevent a descent into chaos. They stood on a chair and shouted in as deep a voice as They could muster to cut through the noise, “Woah! Time out, people!! We need to make a space to check in about what’s going on!” Someone Shay had seen around in the last months shouted in reply, “Not interested in having you boss us about right now!” before someone else who was unfamiliar yelled in jest, “Is that a boy or a girl?!” Shay’s heart sank. Luckily, there was someone to step in and take control; a young hijab-wearing woman called Yasmine, who had previously used the Food Bank and now volunteered to help manage the space. “Shay’s right,” said Yasmine in an assertive tone, “We need to work out what’s going on here! Everyone’s tired – we’ve been doing this all winter, and things are getting worse! So we need to work out how to handle this together! So, you people at the back, can you please say what just happened without making it too long?”

A small white woman shouted insistently, “This guy just pushed in front of me. And he keeps doing it! I’m done with this bullshit. I’m not going to take crap from these people any…” to which Yasmine quickly cut in, “Thanks for sharing, we get the idea.” She then turned to the very tall guy. “So what went on for you?” He shrugged. “I am big guy! I don’t always see the small people. It’s long way down!” Shay caught Yasmine trying to hide a smile. “So what you’re saying is that what just happened was unintentional. Is that correct? So would you be willing to be more careful to make sure you’re not jumping in front of someone when you join the queue?” The guy agreed, and Yasmine asked everyone else to do the same. Phew. Progress had been made. Yasmine was amazing. But things weren’t stopping there. “Does anyone else have anything they want to say about how to handle this situation?” she said.

To Shay’s surprise, an ageing African-Carribean man who looked a little wobbly on his feet said, “Yea, mi do! Mi name’s Khenan, and mi been inna dis country since 1965. An mi neva lose mi accent! Ova di years, mi seen foreignas blamed ova an ova again. Yuh tink foreignas tuh blame fi dis awful crisis, you’ve get anotha ting coming! Mi a old man now, mi work fi Britain mi whole working life, an a few years back dem try tuh deport mi! An now mi cyaan’t even afford anything! Everybody knows dat di energy companies making massive profits while wi cyaan’t pay fi wi bills. Everybody knows dat rent nuh fi be dis high. Mi had enuff mi tell you! Mi tink wi need fi all stay here inna dis centre til di authorities agree tuh mek fi wi living costs affordable again.”

Yasmine looked a bit blank at where to take this radical turn, and Shay sensed They could now step in without facing the same resistance. “Is everyone clear about what Khenan has just proposed?” They said. “Khenan’s proposal is that we occupy the community centre and stay here without leaving until the authorities ensure our cost of living is affordable again.” Someone shouted, “Sure, I’ll do it! At least it’s warm here!” Another said, “Hang about, we need to talk about this more!”

Shay starting organising for everyone in the community centre to meet in the main hall. From there, a team of facilitators quickly grouped together, including Shay and Yasmine, to facilitate a meeting with the purpose of forming a plan of action. A large number of people liked the idea of occupying the centre. Some thought it wouldn’t achieve anything, but agreed that something must be done. They’d occupy until they had won negotiations with the City Mayor. They’d make it high profile in the media and on social media. There would be a call out to mutual aid networks to bring food supplies, bedding, sleeping mats, and items like pallets from which beds could be made for people unable to sleep on the floor. Teams of people would be on a rota to cook, entertain children and keep the space in good order. Anyone who wanted to leave the centre should take their food from the Food Bank and do so before the end of the day. Everyone else must agree to stay for the next 5 days, and then they would collectively review the situation. After several hours, it all came together as a plan. By then, it was 1pm. They would spend until 8pm preparing, after which they would lock themselves inside and start a media operation about what they were doing.

An incredible buzz of activity ensued. People’s sense of purpose and determination thrummed in the building. The call-outs for food and materials rippled throughout the city, and people came to drop off all sorts of supplies. The ex-squatters mastered a pulley system so that as the days wore on and they started running low, fresh supplies could be hoisted up to the first floor and drawn in through an upstairs window. This would prevent the occupation from being compromised through access to the building. By 8pm, they were all just about ready. The doors were closed and locked from the inside, and a huge cheer erupted. The occupation had now fully begun.

The next days in the community centre were what Shay could only describe as the birth of an autonomous zone. One of those most precious moments of life under capitalism, when people had a sense of control of their lives, when there was synchrony in everyone’s actions, when people were no longer atomised individuals rattling around without purpose but were part of something larger than themselves. People cooked up big vats of stew together. Elders played with young children and told them stories. One group of people took to singing around a clanking old piano that someone knew how to play. Another group created banners and other artwork about the occupation to hang outside the windows of the building. And all the while, a group worked on media and social media, tweeting and writing to newspapers and even making TikTok dance videos.

By day four, news came in that six other Welcoming Spaces around the city had gone into occupation. The idea was spreading. Shay’s first thought was that They must find a way to contact the occupiers at the other Welcoming Spaces and start working as a network. The wonders of modern technology meant that Zoom calls were the way forward. It meant that decisions made by meetings in each of the community centres could be shared by spokespeople in a Zoom meeting, and that decisions made in the Zoom meeting could be fed back to the main meetings. In that way, they could work out how to manage the timescale of the occupations, deal with the media and share resources.

By the tenth day, forty-six of the city’s eighty Welcoming Spaces were under occupation, and occupations had spread to Welcoming Spaces in other cities. It was wonderful, inspiring and previously unimaginable. At the same time, Shay knew this couldn’t last much longer. There was no way for so many people to sustain keeping themselves locked up in a building. And there was no way to keep resources flowing to so many different occupations. Food supplies were starting to run low. People were getting tired and ratty. Children were unhappy being confined to the community centre and its concrete backyard all the time, and the media was starting to make a point of how wrong it was.

Of course, the media had changed its tune from the first days of support for the occupiers. News reports were now dominated by interviews with local politicians like the City Mayor, who vehemently opposed the occupations. They achieved nothing, he said; in fact, they were just making the situation worse for all the people who could not access the Welcoming Spaces while the occupation was going on. The Cost of Living Crisis wasn’t something the local government had any control over. They were barking up the wrong tree.

The occupiers had put out their own videos with a counter-narrative. Why weren’t local government and constituency MPs fighting tooth and nail with central government to protect local citizens? Why was the only thing being done to provide these measly Welcoming Spaces?

On day fourteen, the occupations came to an end. Shay got up that morning and staggered into the toilets to find someone trying to fix the plumbing, as no water was coming out of the taps. Not only that, but the lights weren’t switching on. Something was amiss. Shay went into the kitchen to test the gas cooker. No gas. The only conclusion that could be reached was that the City Council had had enough. It was flushing them out.

People in the community centre were outraged when they realised this. How could the Council withdraw basic amenities? Surely, this was against Human Rights? Shay didn’t dwell on this and started calling other occupied centres. Who else had the same problem? It turned out that most of them did. What were they all to do? A plan had to be come up with quickly. There was no Wi-Fi due to the lack of electricity, and before long, everyone’s phones would be out of battery. But there must be a way to turn this situation to their own advantage, and together, they had to devise a coordinated plan.

At noon that day, the occupied Welcoming Spaces across the city opened their doors, and the occupiers walked out, looking weathered but still smiling, to the clicks of journalist cameras. From each Welcoming Space, a procession began, and even people from the Welcoming Spaces that hadn’t been occupied did the same. Local people joined the procession in droves, and Uber drivers, who were on strike at the time, took up the rear, carrying passengers with limited mobility. The processions wound through the city and started to converge with one another. They were heading for the City Council offices, planning to track down the Mayor.

Shay walked with the procession, feeling deeply moved. The impossible had become possible. People who’d been completely screwed over by corporate greed and government were getting over their isolation and taking back control. They were coming together to build something new. What would come next? In a month’s time, would all this have dissolved? In a year’s time, would Shay be joining the ever-lengthening Food Bank queue? Or would something better be establishing its roots and pushing new shoots into the air? The moment that all of them were in was so precious. Yet Shay didn’t want to believe that the moment was only precious because it was so rare. Shay wanted to believe it was because it was the beginning of something. It was fragile and delicate and would take all the energy in the world to nurture it, but at least it was there.

Postscript:

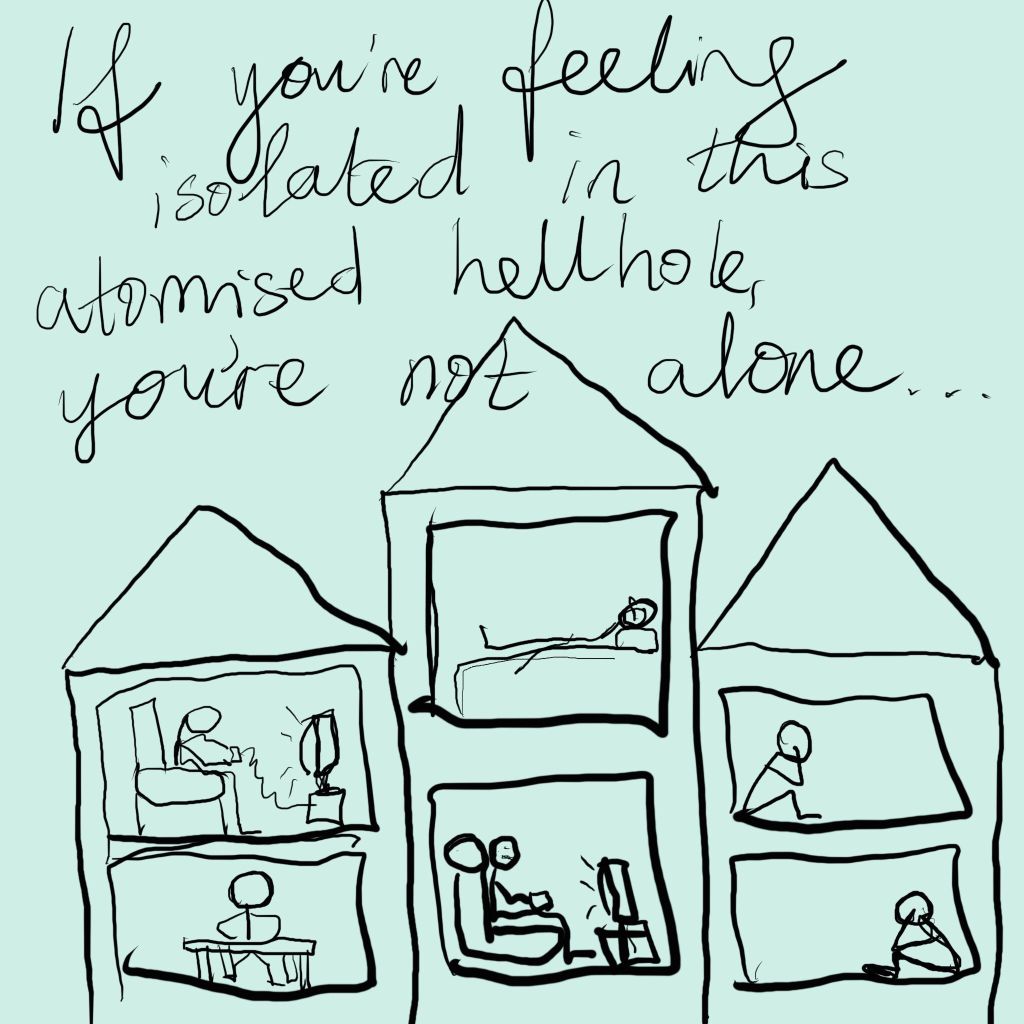

I wrote this piece as a reflection of a dream, a wish, a visioning exercise, maybe even a spell for people to come together and push for changes that address the inequalities and power imbalances we’re facing. We have come to live such atomized, individualistic lives that it’s hard to imagine this happening, which was all the more reason for pushing myself to create a vision of what things could look like. The lead character is someone tough and resilient (which I’m not, so it was fun to imagine being like that), participating in an activist culture which is getting fairly close to being on top of their shit; currently rare, but there’s always hope.

Leave a comment