When Grand-Mère’s will was finally located, her descendants gasped with incredulity at its contents. Even Esmeralda, the favourite grandchild, allowed a ripple of surprise to cross her brow.

Grand-Mère’s offspring had been arduously picking through the contents of her home, shaking their heads and sighing through taut lips. In every corner another pile to sort through. From each shelf, a cascade of trinkets.

The shadow of Grand-Mère looked on from the unmissable shape in the concave of of her ornate antique armchair, the throne of her latter years. The haze of her constantly lit Gauloises, the arch of her haughty eyebrows, the smirk at the corner of her mouth – all hung in the air. Grand-Mère had not left them yet. As she looked down upon them in life, so in death.

Grand-Mère had always been divisive. Her beauty in youth had been spell-binding, and with a flick of her wrist or a shake of her dark and shimmering tresses, those around her were cast to fall down on one side or the other; consumed with love and veneration or with overpowering envy of what had been bestowed upon another. That devastating beauty faded with the years, of course, but by then, Grand-Mère’s dark art of devastation itself had been mastered, and faded beauty mattered not.

She divorced three adoring husbands in her time, when each eventually lost his shine as a photo opportunity. The divorce left each man hollow as a result; one turned to alcohol, another to lost wandering and the third to suicide. It was beyond any of them not to become hooked on the perfection of her social graces; she was the sweetest of nectars, with her laugh in all the right places, her soothing way of fusing back together the jagged fragments of their fragility. When a suitor met with her desires, her words and wiles dosed him into a daze of aggrandizement. When she disengaged, he would be left to whimper and beg in piteous tones to no effect.

Old money made for the formation of Grand-Mère. She held onto her staff like her antecedents from some two centuries previous had held fast to their chattel slaves. Her staff were paid handsomely, making them loyal and complicit.

She bore five children, all raised by nannies who did Grand-Mère’s bidding. Every one of her offspring suffered the pain of her power. The worst thing that could befall a family member was to drop from her favour; to be left clamouring for former privileges. A deluge of attention, adulation, gifts could submerge any of her children, who became heady with the euphoria of their new status before Grand-Mère would withdraw again at some incalculable moment, quick as a card trick.

In consequence, her children grew unable to abide one another, their ties of kinship ever tainted with blood drops at the blade tip of one-up-man-ship. Each vied to be bestowed with the best for themselves; the best room in the house, food at the table, gifts or compliments – each incessantly attempting to win her favour without understanding the main rule of the game; the fickle switch to keep them in vile and petty squabbles between themselves. When a child won out against the others, they would laugh without kindness, poke out a tongue, slam a door in another’s face, laud their triumph in any way they could devise. Over decades this dynamic played its cynical game, holding each child choked in obsequiousness even as adulthood became them.

That day at the house, all five hunted the house for Grand-Mère’s will with the pretence of clearing out the past. Each absurdly believed that somehow her will would favour the one who found it. Reason had never broken Grand-Mère’s spell before, and so why should it now?

Predictably, the eldest was the one to finally locate it; a yellowing envelope tucked at the back of an old Paris Fashion Week special of Vogue magazine. The youngest had already slung the magazine into the discard pile, giving the eldest the opportunity to check her work and chide her for her mistake.

As the eldest held the envelope aloft, the others all darted over from their respective darkened corners of the house. ‘Last Will and Testament’ was elaborately inscribed upon it. The eldest tore it open to find but a single page.

The will turned out to be not what any of them had imagined. The expectation was held between them that Grand-Mère would assign an inheritance to each of them that simultaneously incited jealousy in the others whilst feeling undermining to the recipient.

Instead, Grand-Mère had created a different kind of game for them all; the final twist in her art of divisiveness. The only thing stated in the will was,

‘The first to find the music box will be the keeper of its contents, granting admission to all I leave behind.’

After that initial incredulous gasp, the eyes of Grand-Mère’s offspring all slanted towards one another in mistrust. The moment froze, before shattering into a frantic search to be the One. The house was large and labyrinthine. The music box could be anywhere. There was not a minute to lose.

Esmeralda had not started life as a favourite; in fact Grand-Mère had scorned her as an infant for her chubby limbs and timid nature. But as the years went by, her beauty became as entrancing as the young Grand-Mère; her symmetrical features, her glossy locks, her haughty gait, the potency in her aloofness. It seemed to all that as Grand-Mère looked upon Esmeralda, she saw her own reflection, and began to treat Esmeralda as a natural heir to her power of command. How could Grand-Mère have known that Esmeralda had created her own twist of deception, and at her heart had no intent to extend the dynasty of devastation?

Esmeralda developed her own art over the years – a veneer of cool indifference, never contradicting the word of her grandmother, yet in every moment that Grand-Mère’s eyes and ears were averted elsewhere, held her kin of siblings and cousins in her warm embrace. Whenever Grand-Mère conferred her favouritism upon her grand-daughter, Esmeralda was sure to share the bounty.

While the frenzy of the hunt went on, first for the will and then for the music box, Esmeralda was doing other things. She already knew where the music box was, though she had yet to figure out why Grand-Mère had divulged to her the secret of its whereabouts during her dying breaths.

As she arrived at the house with her mother, aunts and uncles that morning, she headed straight for the attic to find the nook where she had been instructed the music box hid. There it lay, exactly as promised with no games played; shoebox-sized and of smooth, spalted wood.

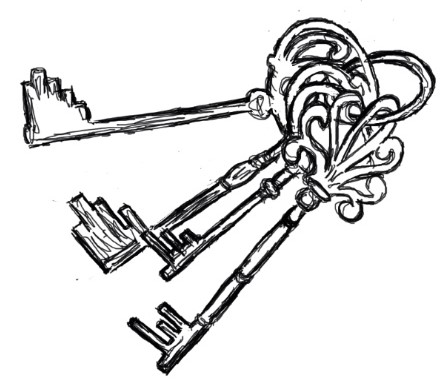

Gingerly, Esmeralda opened the lid, and as she did, a model monkey rose up, wearing a smug expression and brandishing a pair of little cymbals. At the monkey’s feet lay a large set of ancient-looking keys, each adroitly labelled with the window or door to which it pertained. There was a note attached to the main ring that held them together which read,

‘With these, the only original keys to the castle, unused in years, you may make this home your own and yours alone.’

She slipped the box back into its hiding place, inserted the key bunch into her chic little shoulder bag, and crept downstairs. While her relatives desperately searched, she reclined on a faded and slightly musty chaise-longue, leafing through piles of old fashion magazines and reading horoscopes predicting a future that had already long ago come to pass. She bided her time, waiting to see how things would pan out, allowing herself to settle on what should be her next move. From her mother, she periodically received tuts of disapproval, and needling little comments about why she’d bothered to come if she wasn’t going to be of any help. Esmeralda paid no heed.

Upon hearing the furore at the finding of the will and the reading of its contents, Esmeralda decided on her course of action. She began to sidle deftly around the house, locking all the windows with the old set of keys. Meanwhile the frenzy continued around her. When she’d finished with the windows, she went to the back door and slid a key into the old lock, followed by the two side doors. Each key met a lock which was rusty and stiff, and made a grinding, clunking sound as she turned it, yet nobody looked in Esmeralda’s direction as she went about her work. The newer locks, for which a set of keys was held by many a family member, lay alongside the ancient double lock deadbolts, the keys for which now belonged only to Esmeralda. It felt fitting to Esmeralda that Grand-Mère had never removed the old, even as they went unused. There was always some strange contortion in the thinking of Grand-Mère.

Esmeralda then returned to the attic, wound up the music box mechanism, placed it back in its nook and let it start to play. The smug monkey slowly started turning to the tune of ‘Phantom of the Opera,’ its little arms making a jarred movement of the cymbals back and forth. She wondered who would find it first.

Finally, she slipped down the stairs and out of the front door, using the last remaining old key to lock it behind her. As she walked away, she could still hear the calamity of frantic searching from behind the front door. She contemplated what to do with the keys.

Leave a comment