It’s cost Sarah-Lou 50p to lose her last sliver of dignity, and it’s the first and final time I ever see her wear colour.

We’ve all arrived for morning tutorial – still no teacher in sight – and the present moment feels as painful as an instrument of torture. My muscles are tensed, my senses heightened and my breath barely reaches my lungs. The Now feels eternal, so I grip tight to the thought that tomorrow will come and the stiff navy garb we are all forced to wear for the majority of days will return. Until then, I’ll pray that my non-uniform is so close to what the other kids have on that I can fade into oblivion. At age twelve, I already know that the right clothes won’t make me fit in; they’ll just help me not stand out.

Today is the day Sarah-Lou will learn that painful lesson. Her bomber jacket is a swirl of purples and reds, set off by a bold chain-link print design, in a heady clash with her mauve and magenta striped leggings and chunky, oversized high-top trainers. Her hair is crimped into a frizz especially for the occasion, and for some reason her fringe has even more wonk than usual. To finish off the look is a large pair of plasticky-gold hooped earrings. If she were to wake up in a noughties queer night just a sweet decade later, she’d be lauded as the twelve year old diva of the dance floor. Her sense of timing and place is off, that’s all.

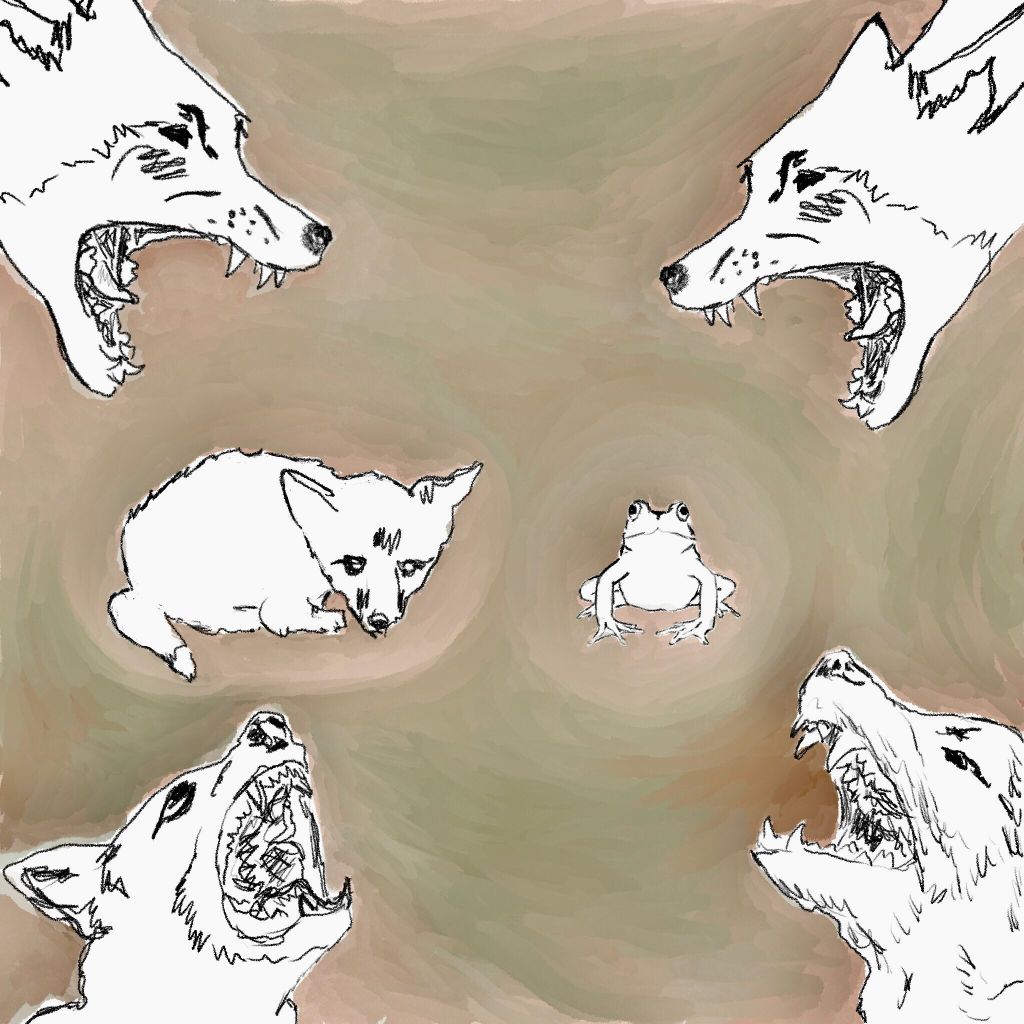

The attack dogs are ruthless. They howl and bay hysterically and rip into Sarah-Lou’s clothes with their mockery. All the while, the top dog sits coolly on her high horse and looks down her nose at the furore. Sarah-Lou, a subdued little fox cub, stares silently into the desk in front of her. I give thanks to an unseen higher power for being left to meld with the merciful background. At the same time, a penetrating thought niggles at my conscience. In my fearful bones I know that I should shake myself out of camouflage into being a real, visible person in the here and now and go and sit with Sarah-Lou.

.

Years later, when we’re no longer in this vicious little hell-hole and via various twists of fate, I will make friends with Sarah-Lou and come to know her brilliant mind and heart and humour. We will spend hours sinking budget bottles of wine with subtle hints of paint-stripper and a sandpaper mouthfeel, all the while delving through our thought processes with the speed and thrill of a loop-the-loop fairground ride. We’ll cover not just banal wranglings with late teenage sex and love, but communism and corruption, crime and justice, asylum seekers and racism and disability. We will never talk about the day at school that broke Sarah-Lou’s colour; it is a silent fact that she will always and forever only wear black.

.

But in the infinite Now, I am at the behest of how thirty-three kids stuck in a room together can spontaneously create the most finessed system of pigeonholing. Everyone has their place, top to bottom, down and out. Nobody is told their rank, we all just Know. Sometimes the top dog swaps over, or a kid gets ravaged when they thought they were safe in their little hole, but mostly it’s pretty fixed. The kids that want to up their status to spend their days pandering to the top dog can do so, but they must endure the gauntlet of her minions tearing into their sense of self to get over the threshold.

The one shred of status I hold for myself is that I’m not as low down as Sarah-Lou, if only by virtue of invisibility. My mind starts to invent reasons not to join her; it’s not that I’m a coward, it’s that I would not stoop so low as to associate with one so clueless and tasteless. Within my fledgling soul, I sense my own wrongness in holding onto being above her. As she stares into the table, I am careful not to allow my senses to edge into what she must be feeling. I resolve to become the most popular girl in school by the time I get to the fifth year, because that is the only way I can see of no longer carrying the weight of being at the bottom, and I will not be able to achieve my goal if I go to sit with Sarah-Lou.

.

If only I knew today that the fifth year will come and I will have blended so fully with the wall that I might as well be stuck inside it. I will come to realise that oblivion hurts as much as any other kind of hell, and people won’t even notice when you’re crumbling. I will understand that I can’t do this any more, because somewhere, deep down buried, I hold onto the possibility that I am Someone and if that’s true, it means I will need to be Seen. But by this point I’ll have no idea how to become unobscured.

The last day of school will finally come and I will not be there to try and get my shirt signed by attack dogs so that I have a memento of what never was. Instead, I will spin off into the freedom of doing a hundred different things. There will be college and uni and travelling and squats and land projects and anarchism and protest and collectives and losing myself and finding myself again. I won’t be at the bottom of the heap any more because there won’t be a heap to be at the bottom of; instead I will be a sand grain in the wind. Any time I spot a heap that I could end up low down in, I’ll be sure to catch the next gust of a breeze and fly free again. My only real resolve will be to never again allow myself to freeze up in a hole.

Sarah-Lou will spin off too, and for years to come we will be grains of sand who wisp by one another, round and round, together and apart, as we twist through life’s great egg timer. By the time we’re in a heap again, life will be over and we won’t give a hoot. I’ll drift distantly from home; she’ll keep much closer, and I’ll wonder why she does that and never think to question why I fly so far away. And as the years tick by, we’ll still have our wine-based explorations, delving into the ebb and flow of the highs and lows.

Sometimes Sarah-Lou will seem to be suffocating under the weight of her work in a women’s refuge, or an alcoholic partner. When things are bad, I’ll notice how her intoxicated talk turns venomous. The asylum seekers are taking our taxes. Disabled fakers are stealing from us all. Single mothers get pregnant on purpose to get a free flat. I’ll come to not mind her saying those things so much, because of how I’ll come to know the heart of Sarah-Lou. I’ll trust that once she pulls herself again from the weight of being near the bottom, her fierce kindness and shining love will return.

And some years on, Sarah-Lou will finally settle, and I will not spin by her any more. She will live near her kin, and have a family of her own. Her choices will confuse me; can’t she see that she’s on a path to being stuck at the bottom again? And I will continue to fly off with the wind.

A day will come in the distant future, when I’m far away from human realms, that I lie on the floor of dry, earthy woodland. I will emerge for a moment from my own waking dream to realise that I have never been and will never be truly at the bottom; my class, race and papers won’t permit it. I will clutch to moss and watch solitary beetles amble by and put my ear to the heartbeat of the earth, which will whisper that my healing will be in standing with those who really are at the lowest part of the heap. I will wonder as I listen if, in another decade’s time, I will have fully shaken off my camouflage; if I will have overcome my fear of really being someone; if I will allow myself not to flee lest I may freeze up again.

.

But today I remain in a pit of raging canines, and I do not yet know these things. Had I the gift of clairvoyance, I’d see that the endless Now of these dogged classroom years could be different; could become a bubble of healing and hilarity with Sarah-Lou, as we bare our grinning teeth back at them, laughing beyond them, laughing them out of existence. I do not move to sit with her. I crouch low, a tender frog in my own little hollow, safe as long as I don’t move a muscle. I hope and pray that they don’t see the throb at my neck.

Post-script: The starting point for this piece was in thinking about how easy it is to ‘other’ one another, and in so doing, we think ourselves superior to those we have othered. I believe this happens namely because of a subconscious projection that those we have othered seem to have less power than we do, so the othering process gives us a false sense of status. I reflected on how this pattern of thinking for me seemed to start in the school classroom. Over the years I’ve found the need to unpick how I’ve subconsciously learnt to ‘other’ people, and the subtle ways that I find myself thinking that I’m somehow better than them. It’s interesting that my own fragility at being low down in a classroom hierarchy didn’t cause me to immediately reject othering, even though I was myself being othered. At the time it felt more important to retain an imaginary shred of status (being ignored was still preferable to being actively bullied). How the richness of life is magnified beyond measure when we finally unlearn our othering; the joy, meaning and connection that we find when we let this falsity go.

Leave a comment