Hadley lies slumped in his faded recliner armchair, head hanging low, jaw loose, the life gently seeping from the flesh and bones of his body. He’s not long gone, and he senses that this next part won’t take much time, but for now, he’s curious to find he can perceive the world around him through his drooped down lids. A sparkle of sunlight is just emerging over the edge of the garden fence, trickling through the foliage. He feels lifted to see his garden just one more time, to have the chance to give reverence to the beloved plants he has spent this life so entwined with.

The garden is more unkempt than usual, due to his decline, yet the final flush of summer flowers is in full swing, thanks to a fortnight of August soaking. His spirit swells to the sight of his finest floribunda roses, the bouganvillea flowers and grapes vining heavily from the trellis outside the back door, the velvety red dahlias. In the back corner of the garden, he sees…could it really be? But he can’t quite tell. He’s not sure if that lick of yellow is just the bright sun. It’s surprising to him that the quality of his vision is no further improved than it was during life.

Maryam will come down from the house upstairs soon, and he feels gladdened that he’ll see her for a final time too. She’s given him such care this last year, like a daughter. He realises that if there was ever a time to wallow in nostalgia, this must surely be it, and casts his mind back to the first time they met. The sensation of a smile ripples across him as he remembers, even if the familiar lift of facial muscles is no more.

She had responded to his scrawly, curled-at-the-sides advert for a room, which he’d left pinned to the noticeboard of his favourite local cafe, amongst a jumble of other notices. Always with the sharpest eye, Maryam. She came over to view the place, but before doing so, he invited her into his ground floor flat beneath the main house to sip pale English breakfast tea and indulge in his best ginger cake. It was always important to get to know a prospective tenant, after all. A mere few minutes passed before they took a dive into disagreement, patterning how things would play out in the years to come. He couldn’t for the life of him think how they’d got to the topic, but for some reason she’d told him she was Somali, not Black.

His retort was whippet-quick – “Child, where on earth you get dat idea? What colour you tink you are den? Bright blue? You as Black as I am, nothin more sure than dat!”

And she’d jumped in, “Somalis are different, you know. We’re not from the same roots as Black people.”

And he’d countered, “Girl, dat make no sense tuh me at all. We all from da same African Diaspora. My roots was detoured via da Carribean before I ended up on dis soggy likkle island, but here I am and here you are and no racist goin ta care if you say you Somali not Black!”

To which Maryam changed tack and snapped, “Don’t call me Girl! And anyway I’m not a child, you know!” Then the tension fizzled and they both laughed at her deflection from her inability to think of a comeback.

At the end of that meeting, Hadley told Maryam he’d be renting her the whole house upstairs for the price of a single room.

“Been empty some time now and me got no interest in no more rowdy tenants – just need a likkle pension top-up ta see me through me final years. Never been able ta get me head roun’ bein a landlord – always believed landlords were bad men!”

Maryam’s head twitched and eyes wrinkled just very slightly as he told her this, but she said nothing. She was never one for betraying herself with expressions of emotion.

He thinks of what a clever girl she is; finishing up at university with a first class honours in Law and sauntering into the big smoke for her first job in a law firm. No wonder she couldn’t stand losing an argument with old man Hadley. She seemed so stiff and serious back then, always with a neatly fitted hijab. These days her hijabwear tends to be a little baggier around the sides.

Another memory of Maryam surfaces, insignificant at the time, but imbued with meaning now.

“The kitchen tap’s broken – you need to come and fix it!”

“I’m an old man – not fixing no broken tap!”

“You’re the landlord, Hadley, you need to do the maintenance!”

“Bah, don’t be foolin’ yourself that landlords be doin no maintenance!”

“Hadley!”

He’d made a point of mumbling and shuffling all the way to the main house, sounding off about his bad knees as he climbed the steps. It was one of only a handful of times in the years that Maryam was there that he went in. He was struck by how bare it was. An espresso pot on the stove top, a couple of pans, a laptop on the kitchen table.

“It’s okay ta spread yourself out you know. You got da whole house, child.”

“Unlikely I’ll be doing that any time soon. More likely I’ll move my three younger sisters in and we can have a room each instead of sleeping in bunks in just the one room like we always did!”

A year or so later, when she called on him again to play the landlord, he saw that things were different. A little softer. Some colourful fabrics were draped around, and photos of family members hung on the wall. It made sense; he’d seen her soften with time. Back when she moved in, she’d strode in and out; early morning to early evening was office and commute time – barely a trace of her, though he’d hear her blathering on the phone to her sisters sometimes, bossing them about and such. Then the Lockdowns came and she started ‘working from home.’ What that really meant, he was never quite sure, and at first he continued not to see much of her.

He was fine and happy that glorious spring, humming to his plant friends as he went about his work in the garden. No need to even leave the house much, thanks to the volunteers that brought his shopping over. Then there came a day in May when he was tending to his floribundas – quite ravishing that year – and somehow his secateurs slipped into his tissue-paper skin. He froze in shock as ruby red fluid streamed from his hand. Maryam must have spotted him from her window and she ran down into the garden with a cloth to staunch the wound. It took an age for the bleeding to ease.

“Old man, you made me scared out of my wits!” she said, finally. “Isn’t it about time you gave this up and got a gardener in?”

“Girl, what you talkin about? I live for me garden!” Her eyes rolled and she sighed heavily at hearing this, but didn’t press the issue.

Instead, she started bringing her espresso pot, full to the brim with a slick of coffee, down to the garden whenever she was on a break. She’d sit on the bench by the trellis as he gardened, framed by the clematis montana flowers, taking elegant sips. He felt irritated at being watched, and one day knocked it on the head by yelling out, “What? Never any coffee for old man Hadley?!”

From then on, she’d bring an extra cup, and they’d sit together for Maryam’s breaks, which began to lengthen greatly. Snippets of precious conversation drift back to him…

“Why do you garden so much?”

“You never without a friend when you garden.”

“But plants don’t even talk!”

“It’s you dat not listenin, child. All da plants always chatterin away, believe you me.”

“You’re crazy, Hadley.”

“Dat one ting I’m not goin to argue with you about. Crazy is how you get by in dis world.”

The edge of her lip curled up when she heard that. Seemed to do that when an idea was filtering through.

“So tell me the names of some of the plants.”

“Well, I’m sure you know the roses. We got these beauties called peonies, and in da back corner, dat lovely flowering tree is a magnolia. Flowers are what make life worth living, you know.”

“And what about that one – the funny bright green one in the other back corner. That one’s got no flowers.”

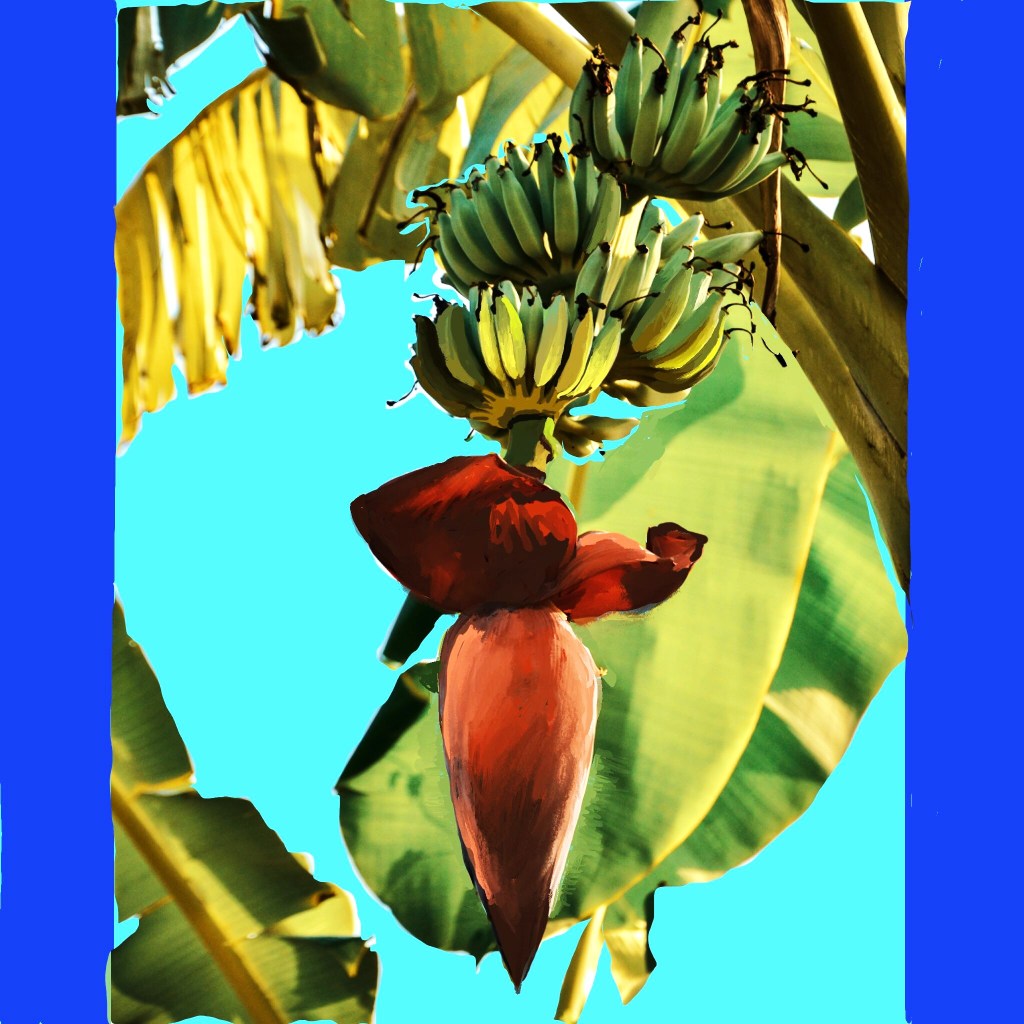

“That one is a banana plant.”

“A banana plant? What, you get bananas growing in your garden?”

“Never till now, but it remind me of me old home long ago, and help me ta live in hope dat one day, bananas will come…”

A silence for some time. Then, “So, young lady – tryin ta remember not ta call you ‘girl,’ but it don’t come easy…so quid pro quo I believe they say…what is it you gettin’ from workin at some fancy law place like you do?”

“I believe in fairness.”

“What kinda law is it anyway?”

“Corporate law.”

“And dat’s what kinda law you really want ta work in? What fairness means to you?”

“I don’t know, Hadley. I don’t come from a wealthy family. Right now, fairness means getting money in the bank, enough for me, my parents and my sisters to do more than scraping by.”

“And what you goin to do when you get enough? Jus’ keep goin like you doin’ now?”

“I’ll start saving the world. Of course that’s what I’ll do.”

Her voice dripped with sarcasm, but Hadley wasn’t having it. “Dat’s my girl, Maryam! Goin ta save da world!”

Hadley’s thoughts emerge from the thicket of memories. Worry rattles him that the egg timer is running low. He’s not sure why these moments between life and oblivion have been spent on Maryam and not the other nine decades he’s walked the earth. It must be because Maryam has been his closest person in the final years, as one after another, each and every other person dear to his heart has passed on. What a life he’s lived, he reflects; a life of beauty, of heady Carribean brightness, of lush English green. Tending, always tending – working on estates and in big gardens – in intimate relationship with every plant in a way that the owners of the land never knew. Being outdoors every single day; the only way he knew to cope with the terrible weather was to get out in it.

His mind drifts on to other loves of his life. Images float by of being a young boy. His Mama singing to him; his sister, Kaleisha, wiggling her hula hoop round and round. The vision which never came to pass comes upon him now, of marrying Agape Desmond, of children running round, before she turned round and broke his heart. The old hurt envelops him for a moment, before he finds that all the pain of his life is starting to float away, disappearing like smoke into clear bright air; the rejections, the betrayals, the stabwounds of racism – all leaving him now.

Then memories of laughing with dear old friends – all of them gone now – surface up. He goes on to picture Jennifer Brown, the only white person he’d ever known pass anything on out of sheer generosity of heart. Landlady turned friend, and when she was gone too, he was astounded to find she’d left him the whole house. He never moved up to the main house – was always happy in the small flat at the bottom. Felt closer to the flowers that way.

As he’s engulfed by the swirl of memories, he hears the key turn in the lock of his front door. He feels a surge of joy and gratitude that Maryam is coming in to make him tea and breakfast before she starts work. Such a shame not to enjoy it. So sad that they won’t be bantering again this morning.

She closes the door gently behind her. “Old man, have you been asleep in your chair all night again? I’ll have to start putting you to bed if you’re not careful!” She comes round to the front of the armchair and gasps at what she sees.

Hadley realises he hasn’t the faintest idea how Maryam will react to his death. He’s never stopped to think that the depth of love he feels for her is actually reciprocal. Hasn’t he always been that pain-in-the-ass old landlord that takes her money, takes the mickey and yet she’s somehow found herself obliged to look after him?

He wants her to know that he appreciates everything she’s given him. He’s left his will on the coffee table – had the feeling last night that it might be the last, and managed to fish the will out of a drawer. He hopes her quick eye will spot it to realise that he’s left everything to her.

But the papers are invisible to Maryam. She drops to the floor with a wail, sobbing like he could never have imagined. Holds one of his heavy hands in hers.

“Old man, don’t leave me…I can’t bear for you to go. I’ll feel so much more alone!”

He’d weep with her if he could, and his spirit whispers, “Jus remember what I told you…go an’ listen to da plants, child…”

Eventually she raises herself and he thinks that now must be the time she’ll call for an ambulance. But instead she goes out into the garden, taking up his decades-old secateurs and a basket from the back porch. She picks her way around the garden, snipping flowers and grapes. He hears her laugh and he can’t think why.

She comes in again, now gently smiling. “Look, Hadley! I picked baby bananas…look! They’ve grown! You were right to have hope!” The lick of yellow – it was true – bananas could grow in this dismal weather after all, if they had the right love and attention.

She lays the flowers around him; garlands round the crown of his head and his neck, then cups his hands one over the other and places the tiny bananas there. At his feet she places the grapes.

As she does, Hadley realises his spirit is drifting up and away. He looks down from above at the hommage Maryam has made to him. She’s saying a prayer now. He’s never really heard her speak Somali before. Further and further he drifts, until Maryam is gone and so is he.

Image credit: adaptation of a photo by Madib zikri on Unsplash

Thanks to Sue Creasey and Rachael Goddard-Rebstein for editing help

Leave a comment